NHS England has published a Long Term Workforce Plan which sets out actions over the next 15 years aimed at tackling the NHS workforce crisis in England. RCOphth Policy Manager Jordan Marshall assesses the implications for ophthalmology and the unanswered questions.

RCOphth and all parts of the health sector have long-called for greater clarity around workforce planning. The publication on Friday by NHS England of the NHS Long Term Workforce Plan therefore comes as a relief, with plans announced to increase medical school places from the current 7,500 places per year to 15,000 places by 2031.

More doctors = more ophthalmologists?

Increasing the pipeline of doctors produced in England can only be a good thing, particularly given the number of people aged over 85 will jump by 55% over the next 15 years. In ophthalmology we already have severe workforce shortages – our 2022 census found 76% of units did not have enough consultants to meet current patient demand – amid long backlogs and ever-growing demand.

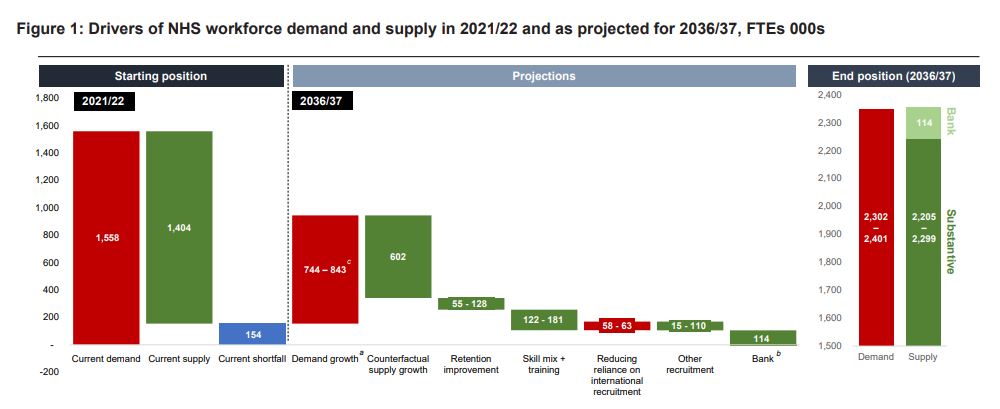

The plan estimates that without any action, given our ageing population, the NHS in England would be left with a shortfall of 260,000-360,000 staff by 2037. Increasing medical school places is therefore a priority, with expansion promised from 2025, reaching 15,000 places each year by 2031 – double the 7,500 number today.

This long term clarity is welcome. Funding has often been the sticking point when it comes to workforce planning however, so it is important to note that the plan only confirms funding for the initial expansion to 10,000 places by 2028. Commitment will be needed from future governments to ensure that this plan is delivered past this initial date.

Crucially for ophthalmology, the plan promises ‘a commensurate increase in specialty training places’ in line with expanded medical school places. This increase will be ‘focused in the service areas where need is greatest’ and outlines the ‘aim to further adjust the distribution of postgraduate specialty training places…a higher proportion of… additional medical students will carry out their postgraduate training in parts of the country with the greatest shortages’.

The commitment to increasing specialty training places in line with medical school places is encouraging for ophthalmology, although disappointingly there is no detail on this yet. Ophthalmology is one of the most over-subscribed training programmes, while in 2021 Public Health England found that England had just 2.5 consultant ophthalmologists per 100,000 population, well below the recommended 3-3.5 level needed to deliver hospital eye services.

We therefore hope and expect to see significant funded increases to the number of ophthalmology training places. The plan points to two key reasons why they did not cover specialties in this iteration: that ‘available data is not yet sufficiently granular’ and the challenge of predicting ‘which specialist roles will be most in demand in 15 years’ time’.

NHS England has been keen to stress that this workforce plan is ‘iterative’, with a promise to refresh the plan every two years in light of new data. RCOphth will therefore work with training programme directors and NHS England to establish what increase in training places is viable and needed to ensure we can better meet patient need into the future.

Retention drive focuses on more flexibility

The image above summarises what the Long Term Workforce Plan is hoping to achieve – solving the current workforce shortages by 2037. You will notice that retention plays an important role in this, with NHS England projecting that their actions will decrease the leaver rate from 9.1% to 7.4-8.2% over the period. This is equivalent to retaining up to an extra 128,000 staff (full time equivalent).

This will not be simple to achieve – our census found 67% of ophthalmology units in the UK had found it more difficult to retain consultants over the previous 12 months – so it’s worth examining some of the ideas to improve retention.

There are two proposals aimed at making it easier for recently retired doctors to return to practice:

- An NHS Emeritus Doctor Scheme will be introduced from Autumn 2023 which allows recently retired consultants (who hold an active registration on the GMC specialist register) to offer their availability to trusts to help deliver outpatient care

- By 2024 the government ‘will introduce reforms to the legacy pension scheme so staff can partially retire or return to work seamlessly and continue building their pension after retirement if they wish to do so’.

Once published, we will share more details on these proposals to make it simpler for recently retired consultants to return to the workforce.

At the other end of the workforce, the plan notes that there should be ‘more flexibility and a broader range of career pathways available to the medical workforce from early in their careers’ – mixing clinical responsibilities with education, leadership, management and research roles. RCOphth supports this ambition, although backing from NHS organisations will be crucial in making it a reality.

Helping SAS and locally employed doctors to progress is included within the plan too, with NHS England emphasising their work ‘to support SAS doctors to have a better professional experience, by improving equitable promotion and ensuring options for career diversification’. RCOphth is committed to supporting SAS doctors in ophthalmology, and is also contributing to the GMC-led work to reform the CESR process.

The plan also emphasises the importance of NHS organisations getting the basics right, such as good quality rest areas, safe storage of personal possessions and food and drink options. It also urges NHS organisations and integrated care systems to ensure e-rostering metrics are reviewed at board level, flexible working options are considered for every job, and investments are made in occupational health and wellbeing services.

One of the reasons that retention has been so poor is that it is inextricably linked to workforce shortages – a recent GMC report unsurprisingly demonstrated that doctors do not enjoy working in environments where they are under more stress and struggle to deliver the best possible patient care. The Workforce Plan does not gloss over this point, acknowledging ‘the influence staff shortages have on organisational culture, and an individual’s experience at work and their decision to leave… increased workforce supply will help achieve the retention ambitions in this Plan’.

Shortening medicine degrees and introducing apprenticeships

Another important aspect of the plan is its ambition to reshape medical education to get doctors into the workforce more quickly. Most striking is the goal of reducing medical degree programmes to four years. There is not much further detail on this, beyond the fact they will ‘meet the same established standards set by the GMC’ and students undertaking these shorter degrees will ‘make up a substantial proportion of the overall number of medical students’. There are also plans for an “internship” model to be piloted in 2024/25, whereby medical students will graduate six months earlier and enter a six-month remunerated internship programme.

The other key announcement in this area was the expansion of the medical apprenticeship route. Aimed at attracting people from under-represented backgrounds, medical apprentices would work and draw a salary as trainee medical practitioners while studying. NHS England will pilot the apprenticeship route from 2024/25 with 200 places, with plans for this to expand so that 2,000 medical students go via the apprenticeship route by 2031/32.

Clearly these will be significant changes, and without much further detail there will be questions about how the same high quality of medical degrees can be maintained with 20% less time given the packed curriculum, and how the apprenticeship model can be developed alongside the traditional medical degree route. Focusing on the implications for ophthalmology, we will be seeking clarity in the coming months on what these changes could mean in terms of ensuring that undergraduates get sufficient exposure to ophthalmology.

Changing ways of working: AI and optometry

The Long Term Workforce Plan also covers changing ways of working, in terms of the use of technology and where care is delivered. Ophthalmology is referenced when the plan highlights the potential of artificial intelligence (AI) in diagnostics to improve accuracy and efficiency, while freeing up clinical time.

As an image-based specialty ophthalmology is likely to be a leader in the use of AI, and it will be important to share learnings and best practice across the profession and beyond. We do still need to see fundamental improvements in how to exchange digital images between systems though, and RCOphth is working closely with the College of Optometrists to support the standardisation of ophthalmic imaging systems.

On the subject of optometry, the workforce plan highlights the potential to ‘deliver more eye care services on the high street’ which ‘could help alleviate pressure in general practice and hospital eye services’. RCOphth continues to work with the optometry community to support the delivery of collaborative eyecare services, as outlined in our joint statement with the College of Optometrists on our vision for eye care services. What would really help enable the delivery of joined-up care is the development of a national electronic eyecare referral system (EERS), allowing optometrists to directly refer patients to ophthalmology. An EERS would facilitate shared imaging standards across primary and secondary care, enabling high volume, efficient patient data sharing.

What happens next?

A key takeaway of the NHS Long Term Workforce Plan is that the medical workforce in England will increase notably in the coming years – by 2031 we will have 15,000 medical school places, double the number today. This increased pool of doctors should boost all specialties in the long term, including ophthalmology, with the commitment to ‘a commensurate increase in specialty training places’. These details will be fleshed out in future iterations of the workforce plan, so it is essential that RCOphth now works to establish what increase in training places is viable and needed in ophthalmology.

This type of long term planning is crucial, but it will obviously do little to tackle the current pressures facing ophthalmology units. In the more immediate term, we will continue to make the case to policymakers across the UK that to deliver timely high quality patient care we urgently need investment in NHS ophthalmology services, such as theatre and clinic space.